Jan Kotik (born 1916 in Turnov, died 2002 in Berlin) belongs among few Czech artists whose work has its' own unique position within an international context. An attempt to situate him in the Czech art scene goes not without problems. Kotik's artistic expression has always been very individual and it seems his entire life he has resisted against dogmas. As a result, his work at some point has truly became uncategorizable. Therefore, this unusual "classic" of Czech art is relatively unknown to a broader audience.Through his entire body of work, Jan Kotik was oriented without compromise on Modern art and intellectual flexibility, even at times when Modern art was being forced out of society. The formal rationality in 1950's painting is very much connected with Kotik's typical color fullness into even unity. Even though those paintings remained long hidden in the studio, his theory and way of thinking finally found its way out to the public sphere. Thanks to various activities such as his collaboration with a glass maker, being head of the studio of industrial design, and as an editor for Tvar magazine, Jan Kotik was able to stand against the doctrine of Socialistic Realism with his own open-minded modern conception.

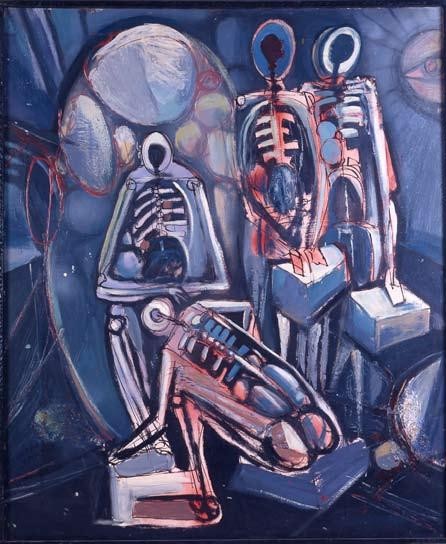

Kotik's works from the second half of the 1950's are comparable with foremost international artists of that time such as Danish born Asger Jorn, Carlos Saura from Spain, Achille Perilli from Italy, or American Arschile Gorky. Not only in the way of formal resemblance, but mainly as an understanding of himself, of themselves as artists with a public mission. In that time context, Kotik's radicality, directness, and abrasiveness presented itself as a unique expression within the Czech scene. The 1957 exhibition of his work at "The Gallery of Czechoslovak Writers" had started critical discussion even on the pages of the daily news, with the official cultural politic about the position of art in society and its right to freedom. This discussion in fact ended after August of 1968.

Kotik's works from the 1960's show obvious conceptual orientation in painting, particularly because he began to concentrate much less on what or how he was going to paint, and more on the fundamental questions about what an image is in itself. A painting doesn't just hang on the wall, it is not just decoration, but becomes a part of the mind and mental development. In 1970, during a fellowship under the invitation of the German state foundation DAAD, he and his wife were deprived of their Czech citizenship and so stayed in Berlin where he died.

His artistic experiments during that period are positionable in the context of Conceptual and Minimalist art in very reduced forms. Several of the series of drawings he completed in the 70's strongly show his attempt on one side to free painting from metaphors and hidden in a direction towards minimalist abstraction. On the other hand, he still insists on developing this idea of the material experience and disturbs, through involving the flatness of the surface plane of the wall into the painting and its originality. In this way he has remained a European artist, revealing his skeptical thinking opposite that of the abstract with its sometimes ruthless principles held by American art from that time. The extension of painting into a new non-rectangular spacial dimension is comparable to contemporary attempts by the Italian painter Emilio Vedova, even though it comes from a different tradition. In the 1980's, Kotik collaborated in Berlin with some of the young German artists for example Hermann Pitz and Raimund Kummer, which showed how his experimenting would look and which became wholly synthesized in the actual and new generation of that historical milieu.

Through his entire body of work, Jan Kotik was oriented without compromise on Modern art and intellectual flexibility, even at times when Modern art was being forced out of society. The formal rationality in 1950's painting is very much connected with Kotik's typical color fullness into even unity. Even though those paintings remained long hidden in the studio, his theory and way of thinking finally found its way out to the public sphere. Thanks to various activities such as his collaboration with a glass maker, being head of the studio of industrial design, and as an editor for Tvar magazine, Jan Kotik was able to stand against the doctrine of Socialistic Realism with his own open-minded modern conception. (jirisvestka.com)